I have created hundreds of current-state and future-state business process models across pretty much every industry, business function and type of organization (public companies, private sector, government). My experience is that there are a core set of business process modeling best practices that apply regardless of industry, business function or type of organization.

The focus of this blog is on that core set of best practices for modeling business processes, not on analyzing business process – that is the subject of an upcoming blog post. However, modeling a business process, both current state and future state, is essential to the successful analysis of business processes.

Note: for the purpose of this post the term process model and process map are used interchangeably.

Components of a Business Process

There are two core components of a business process – work activities and workflow.

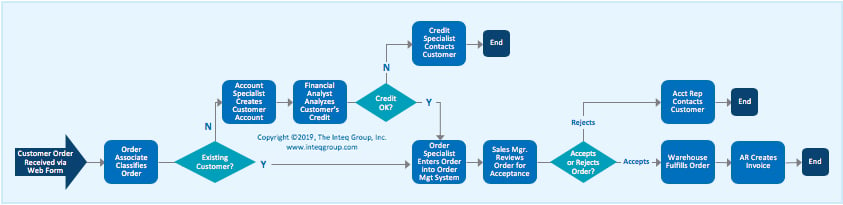

A “work activity” is a cohesive unit of work performed by an actor (person or system) that transforms inputs into outputs in accordance with a set of business rules (formal or informal). Work activities are where the actual work of the process is performed. For example, some of the work activities in the Order Fulfillment process (see process map below) are Order Associate Classifies Order, Account Specialist Creates Customer Account, Sales Mgr. Reviews Order for Acceptance, etc.

A “workflow” is a sequence of work activities that result in an end point in the process. For example, the four work activities Order Associate Classifies Order, Account Specialist Creates Customer Account, Financial Analyst Analyzes Customer’s Credit, and Credit Specialist Contact Customer are a workflow in the Order Fulfillment process.

A business process then, simply defined, is the end-to-end set of work activities and associated workflows.

10 Business Process Modeling Best Practices

1. Just the Facts

Do not try to analyze a business process or suggest ideas for improving a business process while you are trying to understand and map the current-state of a business process. The objective of current-state mapping is to deeply engage subject matter experts (SMEs) and other stakeholders to develop a thorough and accurate depiction of the current state. Attempting to analyze and improve a business process before thoroughly understanding the process compromises the objective of current state mapping and creates credibility and trust issues between you, the business analyst, and your SMEs and stakeholders.

For example, while you are engaging your SMEs and stakeholders in mapping the current state, you throw out an idea to improve the process – saying something like “how about if you tried this rather than this thing you are doing.” Even if your idea is a good idea, one of your SMEs or stakeholders has probably already come up with that idea but was not able to move it forward – and they will be resentful of you putting forth their good idea. And, if your idea is a bad idea, the reaction from your SMEs and stakeholders will be – in their mind, not verbally, “this person does not know enough about our business and processes to know that it’s a bad idea” – and you lose credibility.

2. Get the Right Story

Ensure that as a business analyst, you engage a representative balanced mix of SMEs and stakeholders. There is often a disconnect between how managers perceive that a process is performed and how the process is actually performed. Accordingly, I typically start by engaging the people that actually perform the majority of the work activity in the processes – typically front-line staff and supervisors – and then work my way up to managers and leadership as appropriate to confirm, verify and provide additional insight into the process.

That said, it’s also important to understand that there can be multiple “right” stories. If, for example, two or more people are performing the same work activity in a business process, there will typically be some variation in how the work activity is performed among those people. If the same business process (e.g. recruiting, customer billing, etc.) is performed independently in multiple business units or divisions of an organization, there will be variation in how the process is performed among the business units or divisions.

3. Cross the Scope Boundaries

Some mapping initiatives are scoped very tightly – perhaps only a few workflows that are part of a much larger business process. Some are broader in scope such as the workflows spanning multiple functional areas, but not the full end-to-end process across the enterprise.

If the scope of the mapping initiative is not end-to-end cross enterprise that also includes external touch points with, for example, customers, then go a bit further upstream and downstream in mapping the process than the defined scope of the initiative. There is at least one work activity upstream that the in-scope part of the process is dependent upon. There is at least one activity downstream beyond the scope of the process boundary that is dependent on the in-scope part of the process.

The process map is not sufficiently complete for proper end-to-end analysis if the one-up and the one-down work activities across the scope boundaries are not included in the map.

4. Deep vs. Superficial Mapping

The key is to create a process map at the right level of detail that tells a story at the right level of detail and that SMEs and other stakeholders intuitively grasp and provide a biases for sophisticated objective analysis. My experience is that far too often process maps are too superficial to tell the story at a sufficient level of detail to enable SMEs and other stakeholders to 1) challenge the validity of the map during process mapping and 2) enable identification of actionable gaps and pain points during analysis.

Occasionally, process maps are too detailed to enable participants to clearly see the end-to-end concepts. This is typically the result of an analyst falling in love with the current state map and the current state mapping processes - and losing track of the goal of mapping a business process. That said, my best practice guidance is to err towards too detailed than too superficial.

5. Use Standards

I have reviewed about every type and style of process map that you can imagine. I find it particularly interesting (or entertaining if you are a cynic) and at the same time disconcerting, when I review a map that was created using a set of ad-hoc symbols – squares, circles, triangles, parallelograms and even lightning bolts, images of a truck, etc.

When I ask the person that created the process map using their ad-hoc symbols what the symbols represent, they have a hard time defining the symbols in a consist, coherent, cohesive manner. Accordingly, the map is not intuitive and not consumable by the SMEs and other stakeholders that were involved in the formal process mapping sessions, let alone the people that were not part of the session.

One of my litmus tests for a useful process map is that when SMEs and other stakeholders view the map, they immediately, instinctively, and intuitively “get” the process without explanation from the business analyst that created the map. The only way to create a map that passes the litmus test is to use an industry standard process mapping approach and associated symbols. My preference is Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) maintained by the Object Management Group. However, there are several excellent industry standards.

6. Get the Baseline Right

Business processes have three types of workflow paths through the process - the baseline path (aka the standard path or “happy path”), alternative paths and exception paths. There is always a baseline path and there is only one baseline path. There are typically one or more alternative paths and one or more exception paths.

The baseline path is the sequence of work activities based on the most common outcome of conditions (the decision diamond symbol). That is why the term “happy path”, while frequently used in conversation, is a bit of a misnomer. Frequently, the most common outcome of one or more conditions is not a preferred or “happy” outcome, but it’s the most common and therefore lies along the happy path.

It’s essential to map the baseline path first and to get the baseline path “right.” The baseline path is the spine of a business process and other paths/workflows are extensions of the baseline path. If the baseline path is not mapped correctly, the deviations from the baseline path (alternative and exception paths) will not be correct.

Alternative paths are workflow sequences that deviate from the baseline path, but eventually route back to the baseline path. Exception paths are workflow sequences that deviate from the baseline path or an alternative path, but eventually reach an end point other than the baseline end point.

In the process map above, the baseline path is the work activities “Order Associate Classifies Order” > “Order Specialist Enters Order into Order Mgt System” > “Sales Mgr. Reviews Order for Acceptance” > “Warehouse Fulfills Order” > and “AR Creates Invoice.” There is one alternative path and several exception paths in the business process map above.

7. Some Secret Sauce

The secret sauce to creating a thorough and accurate process map is the use of break-fix scenario analysis. The general concept is to engage the SMEs and other stakeholders by challenging them to identify business scenarios that “break” how the map is currently modeled. In other words, the work activity and workflows do not support the scenario identified by the SME or other stakeholders. The map can then be revised to support the scenario.

The dynamic is this – people (SMEs and other stakeholders) are generally fairly good at identifying the baseline path as well as alternative scenarios and exception scenarios that are standard and frequent. However, what people are typically not very good at is identifying alternative and exception scenarios that occur regularly, but not frequently. These are the non-standard scenarios that if not identified during mapping and therefore not analyzed during analysis, are not properly supported and optimized for the future state.

Break-fix analysis really lights-up people’s brains. It’s the best way that I have found to enable people to dig deep into their experience and subject matter expertise and mine that deep business knowledge. People love to “break” things in mapping sessions – it’s just human nature. A word of caution, however – be aware of exotic and hypothetical scenarios. These are scenarios that have never happened and likely never will happen. A business analyst can burn a lot of time mapping exotic and hypothetical scenarios that add little or no value to the map in most projects.

8. Workflow or Swim Lane?

The two most common approaches to the layout of a process map is the workflow view or the swim lane view. Both are excellent approaches. The process map above is presented as a workflow view. The baseline path is depicted left to right and the alternative and exception flow deviates from the baseline and is depicted left to right as well.

A swim lane view (reminiscent of swim lanes in a lap pool) is an approach that lays out the process map from a functional view. A swim lane is created for each functional area that contains an activity in the process flow. A swim lane view clearly shows the functional ownership of a work activity and the cross-functional handoffs in the process.

A swim lane view is an excellent approach to laying out the business process if the process has a high degree of thrashing – the flow moves in and out of many functional areas repeatedly. Vertical lanes can be added to a swim lane diagram to depict the time frame in which the activities normally occur.

It’s important to understand that a swim lane view is simply an approach to the layout of a process map – just as the workflow view (standard path, alternative paths, and exception paths) is simply an approach to the layout of the process map. The same concepts of activities, conditions, relationships and events apply to both approaches. It’s just simply a choice by a business analyst regarding the layout of the process map.

If a business process is reasonably well behaved (a sequence of activities is performed in one functional area before transitioning to another functional area), then the workflow view is an excellent layout approach. If the process has excessive thrashing across business functions, then the swim lane view is an excellent layout approach.

9. The Tool Myth

There are many excellent business process modeling and analysis tools in the market place. And, my experience is that they are all pretty good – albeit some better than others. My point, however, is that the magic in process modeling and analysis is not in the tool, it’s in the skills, competencies and expertise of the business analyst mapping and analyzing a business process.

An expression that someone mentioned to me a number of years ago is that “a fool with a tool is still a fool.” In other words, just because someone has access to a great tool and creates great looking maps, models and diagrams, does not mean that the maps, models and diagrams are accurate or useful. Accurate and useful maps require a highly skilled business analyst.

That said, in the hands of a highly skilled business analyst, a process modeling and analysis tool is an excellent investment. A tool can increase the speed of mapping and analysis and provides an excellent store of business knowledge. Tools range from generalized visual drawing utilities such as Visio to specialized, full-on repository based multi-user platforms.

10. Walk the Walk

When you get to the point that you have a stable validated process map, go out into the actual work environment and walk the map from end-to-end. There is significant value in walking the map when, but not before, the map is stable and validated. Sometimes SMEs and stakeholders try to minimize their time engaging in formal process mapping sessions by asking the business analyst to simply shadow them and ask questions while they work. While these SMEs and stakeholders are typically well-intended, my experience is that shadowing is ineffective in creating a process map, but highly effective in refining a process map that is created via formal mapping sessions.

The dynamic here is that as a business analyst, you do not know or have context for what you are observing while shadowing prior to mapping a process. However, after you have created a stable validated process map via formal process mapping sessions, you will have a deep understanding of the process. Then, while shadowing, you have the context to quickly spot disconnects between the process map that you developed in formal mapping sessions and what you observe in the work environment. You can then work with the SMEs and other stakeholders to reconcile disconnects.

Today’s rapidly changing business environment favors high-performing, agile organizations capable of delivering extraordinary customer and business value.

Meeting this challenge often requires transformative change - and sustainable on-going improvement in business processes, organizational culture and supporting technologies.

Subscribe to my blog | Visit our Knowledge Hub

Visit my YouTube channel | Connect with me on LinkedIn

Check out our Business Analysis Training Courses and Consulting Services